In one of my previous posts, I have already covered the Russian Genitive case.

After mastering the main functions of the Russian Genitive case, I recommend moving on to the Accusative case. Why? Because these two cases often compete with one another, and even native Russian speakers sometimes struggle to choose between them.

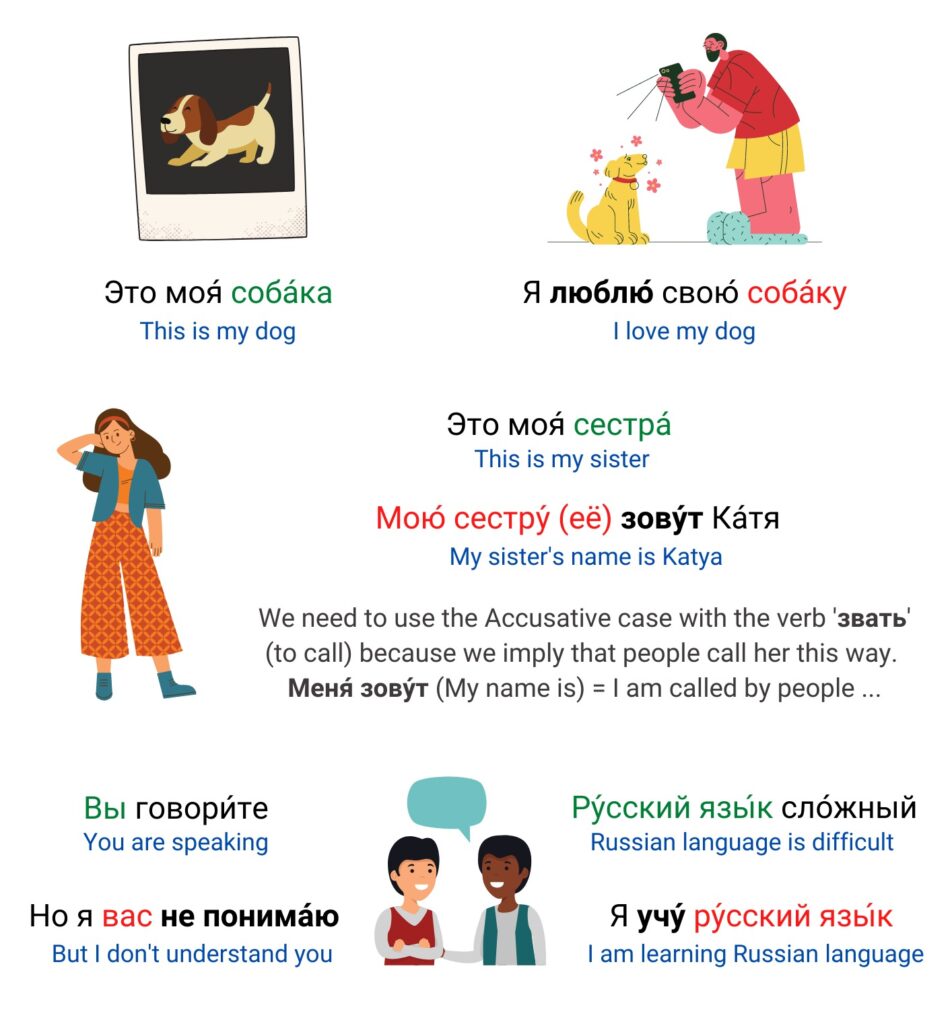

The Russian Accusative case behaves like a chameleon. When used with inanimate objects, it answers the question «Что?» (What?) and mirrors the Nominative case. However, when used with animate objects, it answers the question «Кого?» (Who(m)?) and takes forms similar to the Genitive case, depending on gender.

There are also numerous contexts in which the Accusative case is required to indicate a direct object of an action.

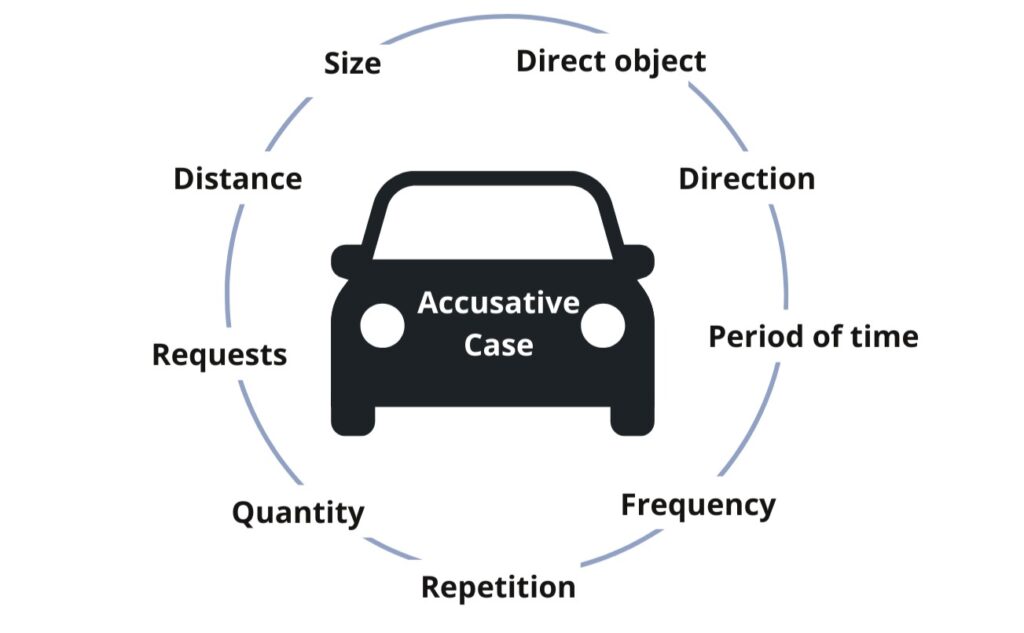

The functions of the Accusative case can be really tricky. To remember them better, you can associate the Accusative case with a car. Just look at the situations when we need to apply it:

Overall, it becomes clear that these situations share many similarities and are interconnected. The Accusative case is also required with a number of specific prepositions and verbs, which you will encounter throughout this guide. As you can see, there are numerous contexts in which the Accusative case must be used, and therefore, mastering it is essential for developing confident and accurate speech in Russian.

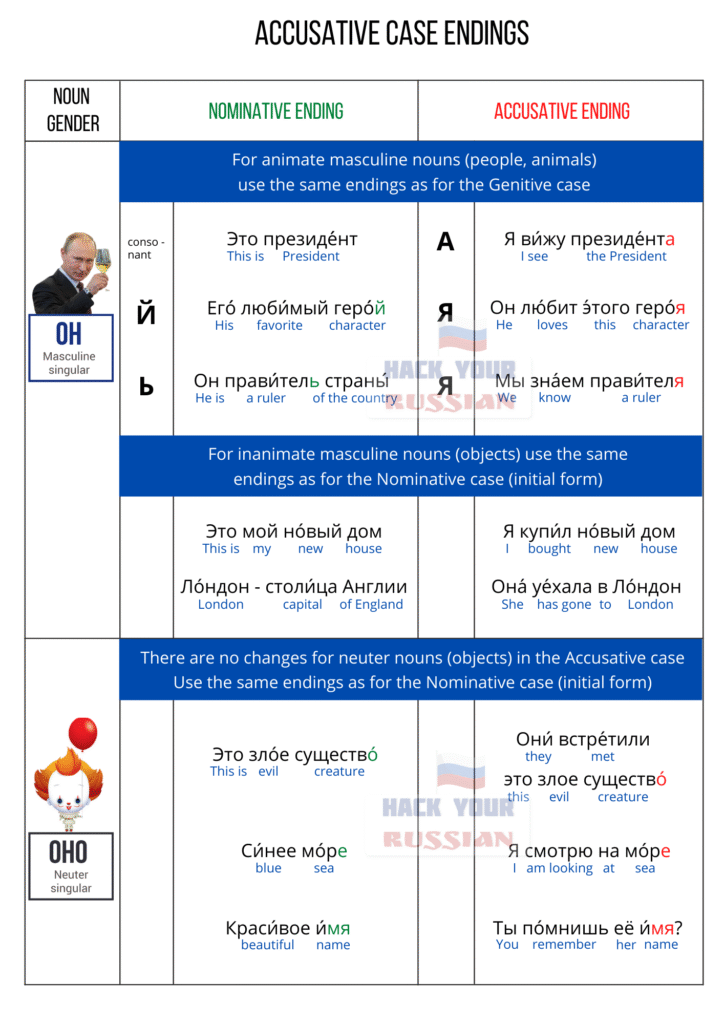

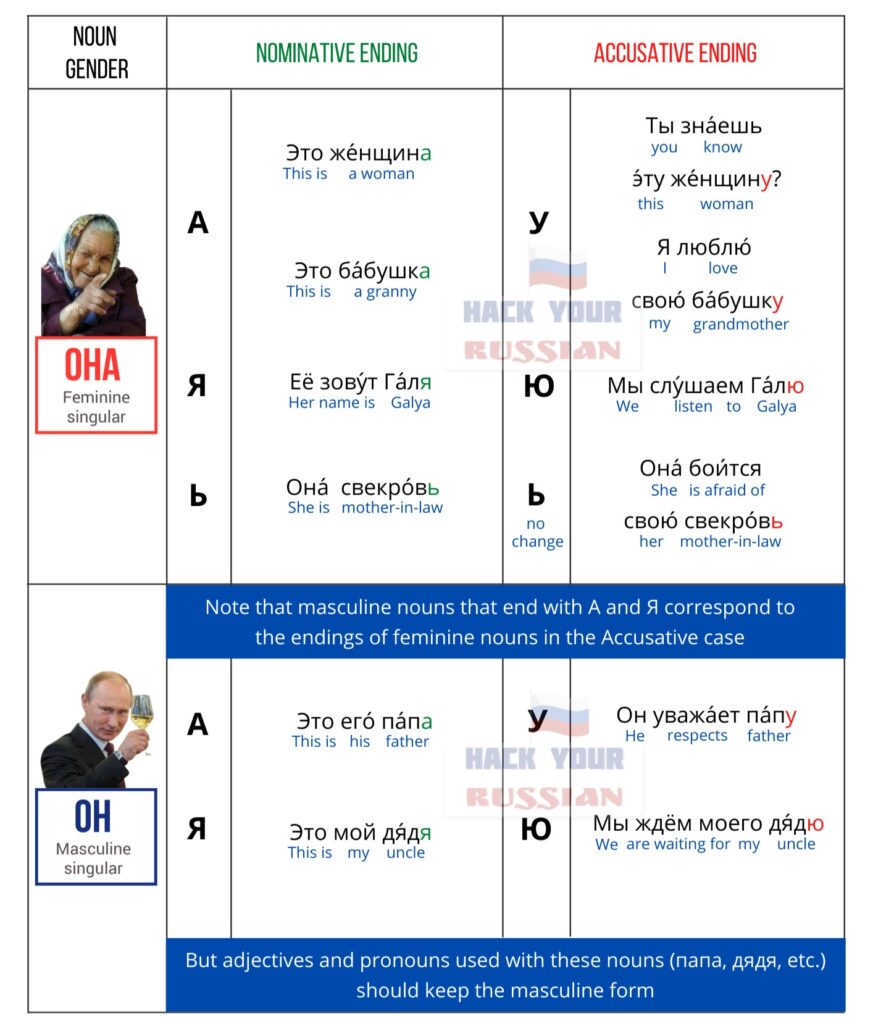

We will begin by examining how noun endings change to form the Accusative case. You will find the necessary tables below. Do not attempt to memorize the endings in isolation – learn them in context, supported by clear examples.

Endings for singular nouns in the Accusative case (with example sentences)

Have you noticed?

Only feminine singular nouns, animate (nouns which name human or animal life forms) masculine singular nouns change form in the Accusative case. Animate masculine nouns take the Genitive case endings in all contexts in which the Accusative case is required. There is no change for inanimate masculine and neuter singular nouns (keep the Nominative form).

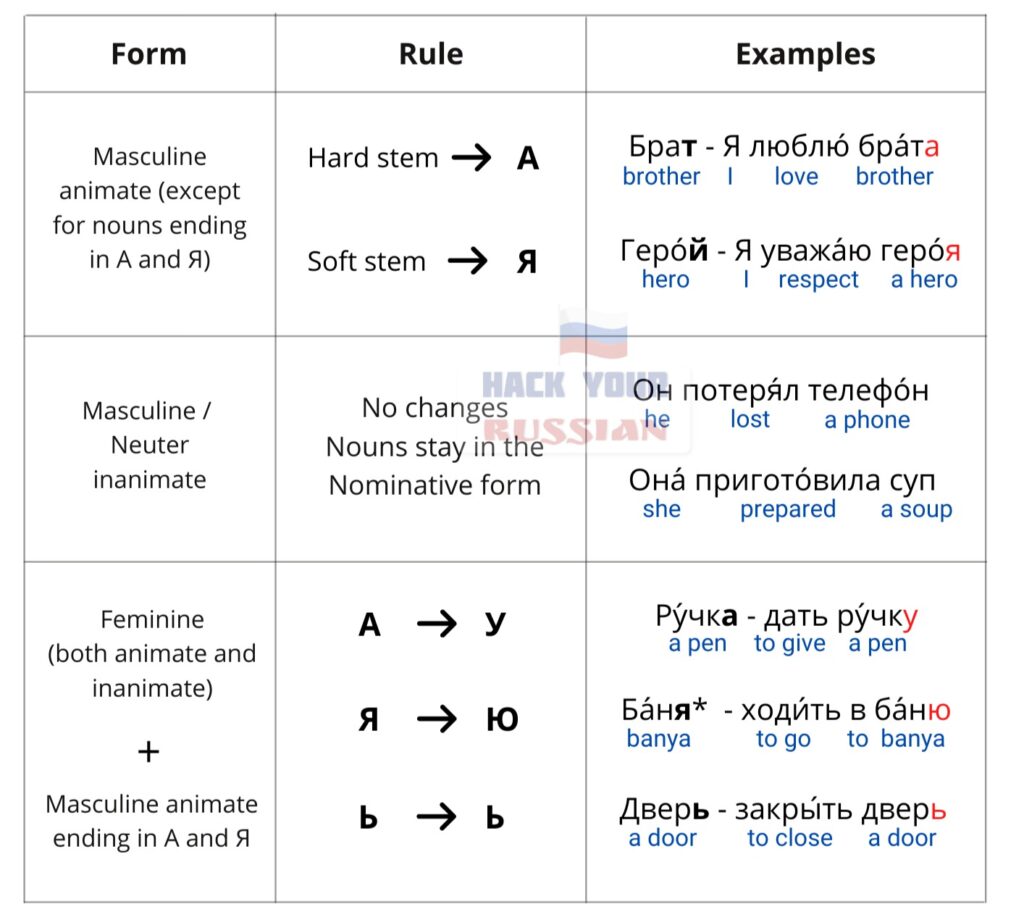

Let’s sum up the Accusative case endings for singular nouns and create a clear system out of it to make it more simple.

Before doing this, let’s learn some important definitions:

- A stem of a word – the whole word without ending

- Soft consonants – consonants followed by the letters и, е, ё, ю, я and a soft sign. The letters ч, щ, й are always soft.

- Hard consonants – all other consonants except for the soft.

You need to know which consonant stands in the end of the word stem to put the correct endings for masculine nouns.

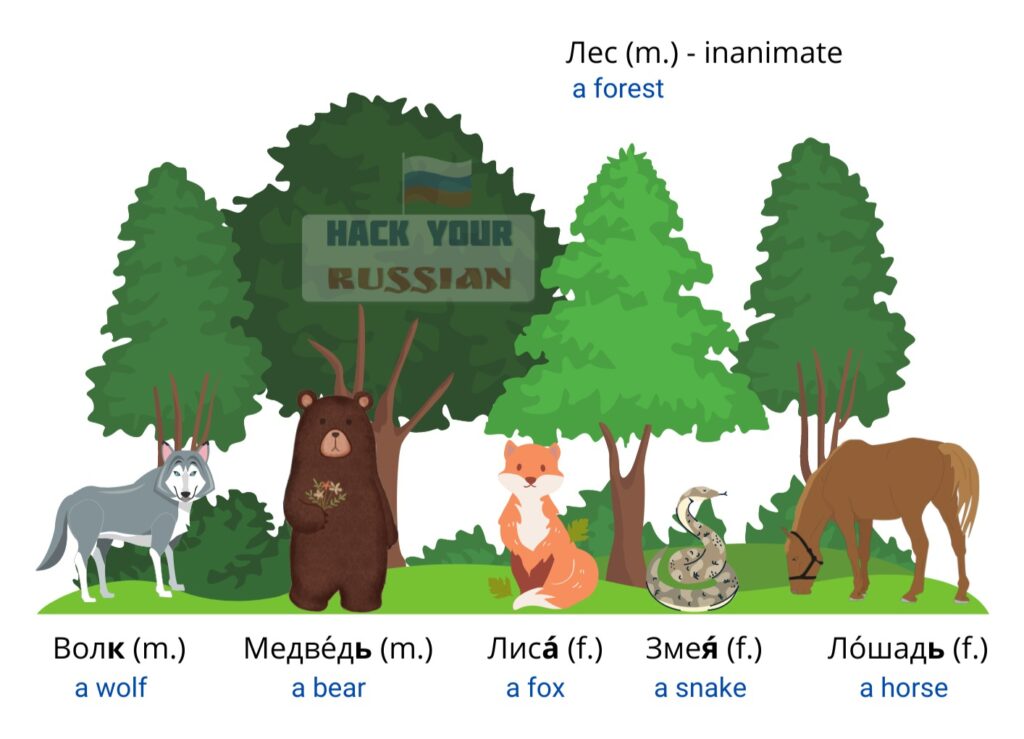

To make it easier for you to remember these endings, memorize them in example sentences. You can create your own or use mine:

Мы пошли́ в лес и уви́дели там во́лка, медве́дя, лису́, змею́ и ло́шадь (We went to the forest and saw a wolf, a bear, a fox, a snake and a horse there).

As you have seen, animacy plays a crucial role in determining Accusative case endings. The general rule states that animate nouns refer to living beings, such as people and animals, while inanimate nouns refer to non-living objects. However, in Russian, this distinction is not always straightforward. There are important exceptions that you must be aware of in order to choose the correct endings accurately.

Some forms of nouns denoting dead people and those creatures, who don’t belong to the world of alive, have the same endings as animate nouns in the Accusative case: ‘поко́йник’ (m.) – the deceased, ‘мертве́ц’ (m.) – a dead man, ‘вампи́р’ (m.) – a vampire. Do you know why? It can be explained by the fact that they were alive before and they still have an image of a living thing.

BUT! Words ‘труп’ (m.) – a corpse and ‘зо́мби’ (n.) – a zombie do not change their endings in the Accusative case as they are considered as inanimate nouns.

Words like ‘ро́бот’ (m.) – a robot, ‘ки́борг’ (m.) – a cyborg,’ку́кла’ (f.) – a doll and ‘матрёшка’ (f.) – a matryoshka are also considered as animate nouns since they have similar features with people.

The word ‘наро́д’ (m.) – ‘a public, a nation, a crowd’ is on the contary considered as an inanimate noun. It can be explained by the fact that this word implies a group of people. The word ‘group’ by itself cannot be animate. Ex.: Он подде́рживает наро́д – He supports the public (meaning people).

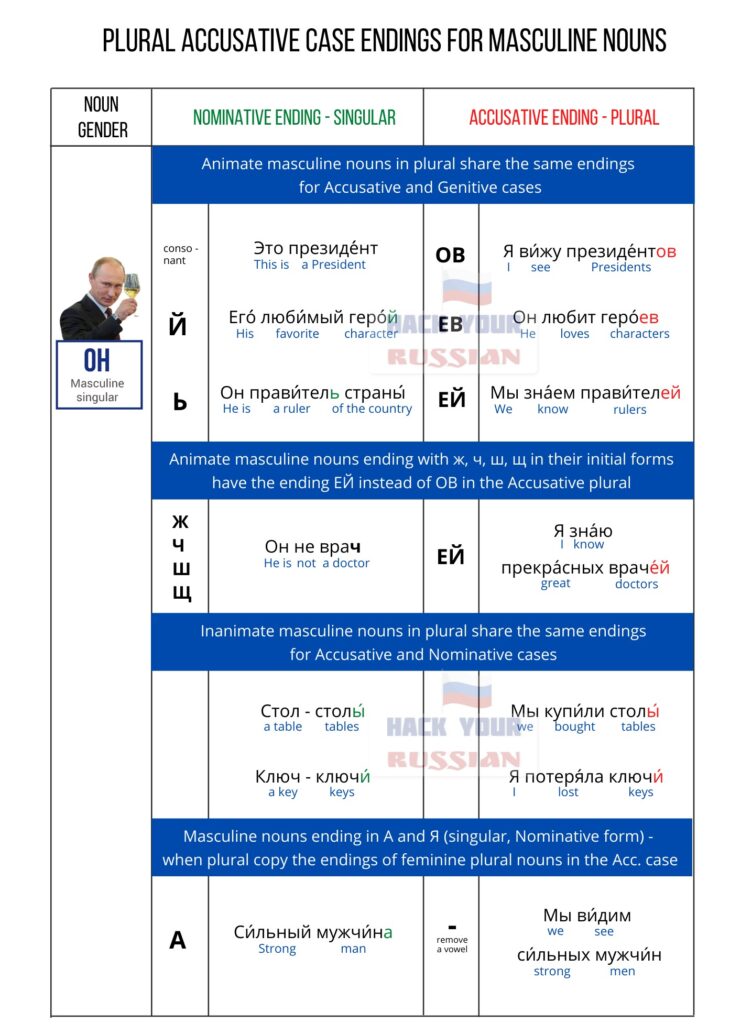

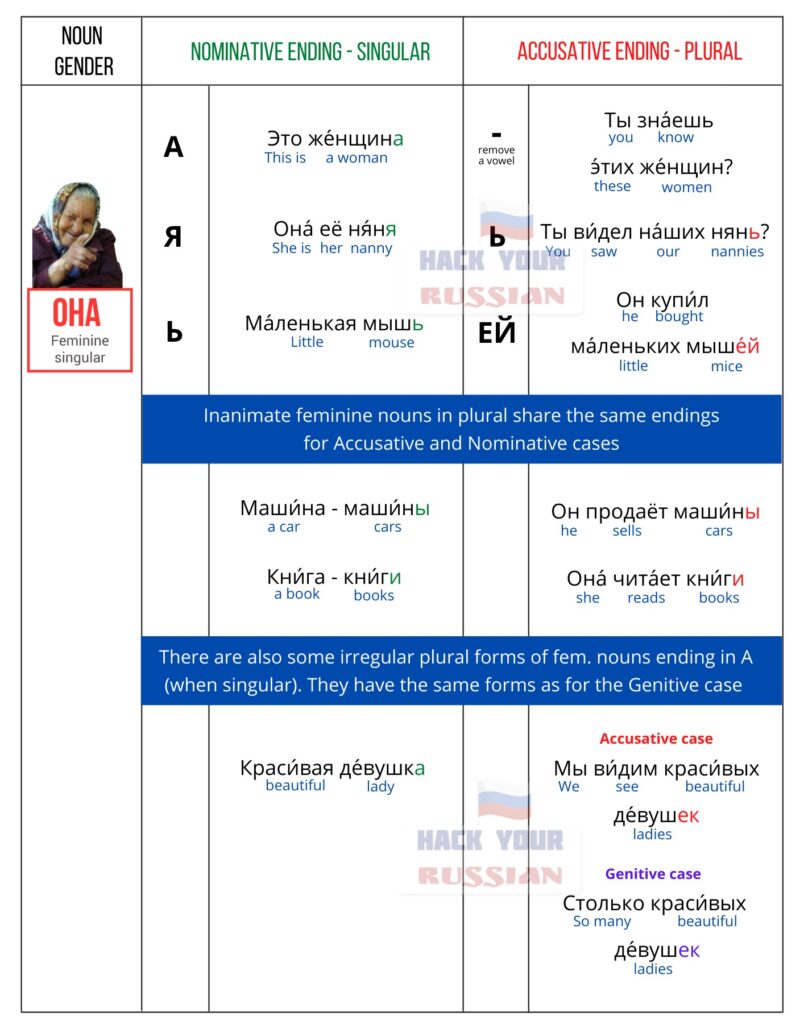

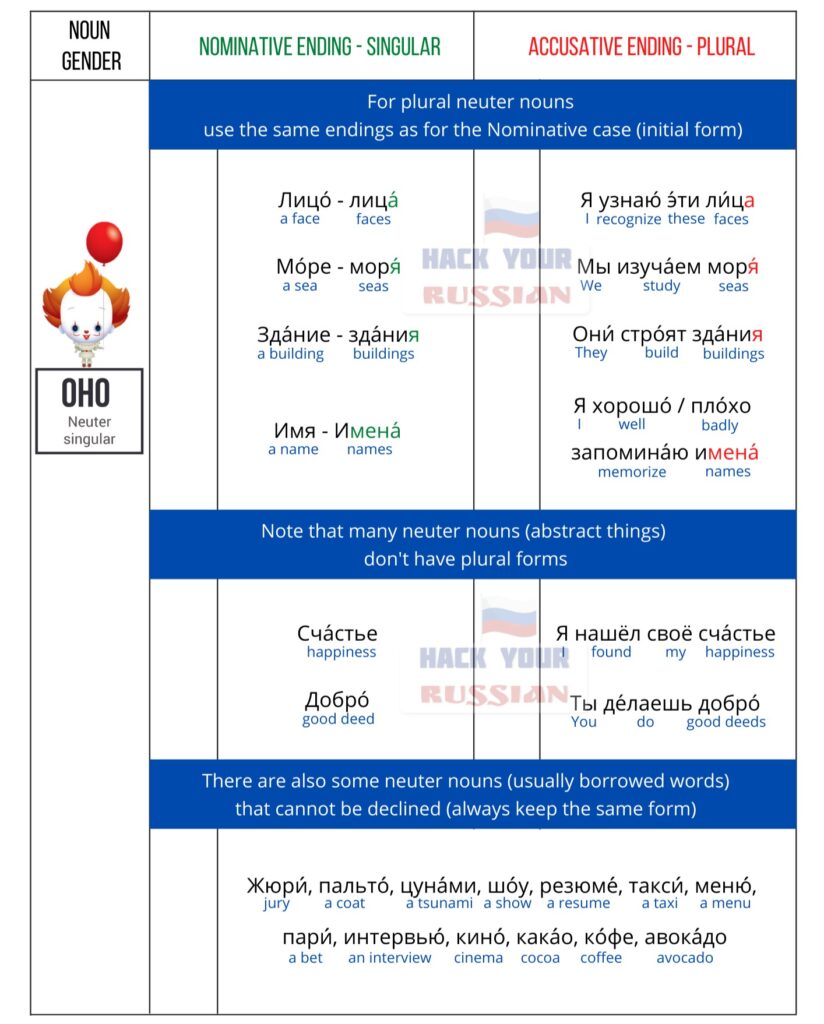

Endings for plural nouns in the Accusative case (with example sentences)

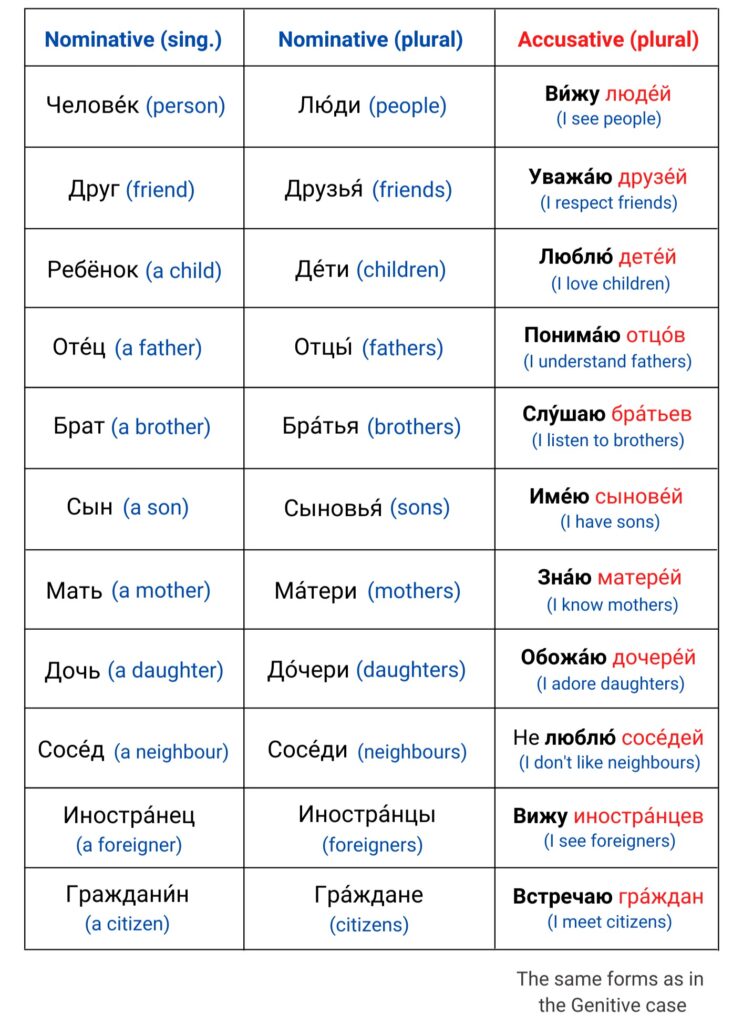

Good news! Only animate plural nouns of any gender change form in the Accusative case (take the same form as in the Genitive case). There is no change for inanimate plural nouns of any gender. But there are also some irregular plural forms of nouns in the Accusative case. Look at the table below.

Irregular plural forms in the Accusative case

So, when is the Russian Genitive case used? Let us consider the most common situations:

- Accusative case: Direct object

One of the main functions of the Accusative case is to show a direct object (object of an action). In simple words, when you have a subject + a verb that requires a direct object (a person or a thing which receives the action of the verb) you will most likely need to put this object in the Accusative case. If a noun is a direct object of the verb, it looks like this:

Subject + Verb + Object (Accusative case).

Let’s compare these contructions with subjects (Nominative, active) and objects (Accusative, passive):

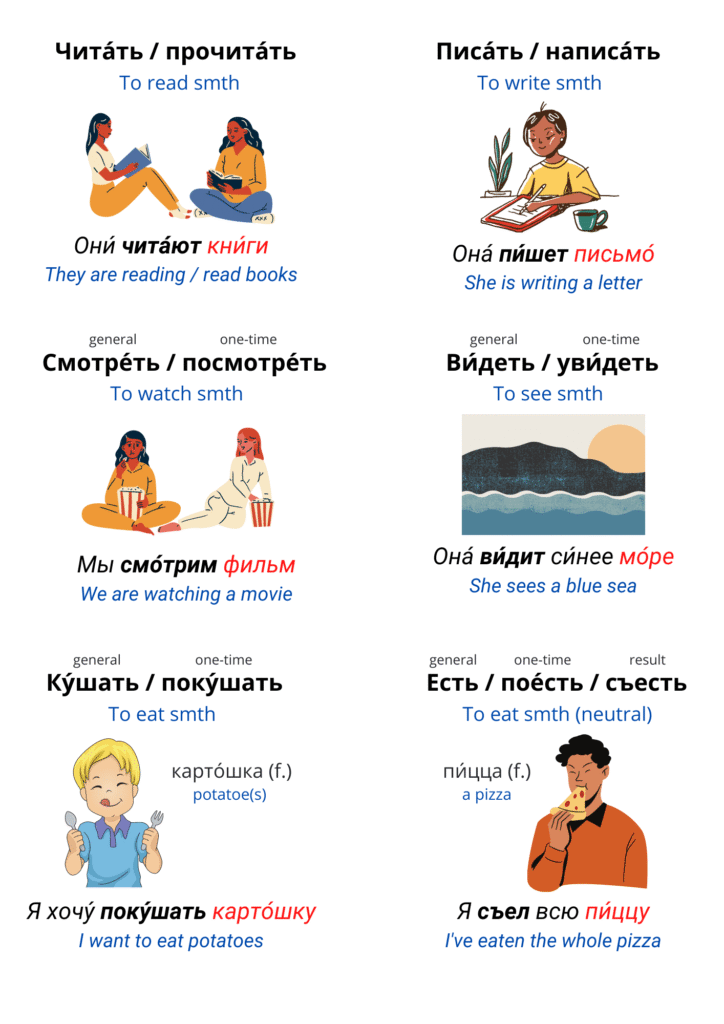

There are lots of verbs that require the Accusative case. They are known as transitive verbs (verbs that require an object to receive the action). Here are some common transitive verbs without prepositions that require the Accusative case.

Verbs that require nouns in the Accusative case

There are also some verbs which are in competition with the Genitive case. In fact, the rule is easy: if you speak about some particular things / people – then use the Accusative case. But overall, even Russian natives make mistakes with these verbs all the time. You can see below such verbs that can be followed either by the Genitive or the Accusative case depending on the context.

- Motion Toward a Destination

With verbs of movement to show direction towards a place. Ex.: Я иду́ в шко́лу (I am going to school).

Note: Prepositions like в, на + Accusative show motion towards.

- Expressing Time and Duration

Used to indicate a specific time period or duration. Ex.: Я рабо́тал весь день (I worked the whole day).

- With Certain Prepositions

Some prepositions require the Accusative case to indicate direction, purpose, or relation.

| Preposition | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| под | under | Кот убежа́л под маши́ну (The cat ran under the car) |

| за | for / behind | Она́ вы́шла за дверь (She walked out the door) |

| через | across / over | Они́ перехо́дят че́рез доро́гу (They are crossing the road) |

| в | in (to speak about games) | Он лю́бит игра́ть в футбо́л (He loves playing football) |

- Expressing Cost, Weight, and Measures

Indicates what is being measured or counted. Ex.: Она́ купи́ла килогра́мм я́блок (She bought a kilogram of apples). Я заплати́л сто рубле́й (I paid one hundred rubles).

- With Days, Dates, and Parts of the Day

Used to express when something happens. Ex.: Я приду́ в пя́тницу (I will come on Friday). Мы уви́димся в сле́дующий раз (We will see each other next time).

You can find all tables and grammar explanations for the Russian Accusative case in the Most comprehensive guide to the Russian Accusative case.

More guides to Russian cases to discover